Many teachers have experienced that anti-climactic moment after executing a lesson plan to precision. Instead of witnessing a flurry of activity from students, you are gazing at a flock of lost sheep meandering around with looks of confusion. What do we have to do? How do we start this? What do we do first? These are questions familiar to many educators. You start to question where you went wrong: Did you scaffold the lesson enough? Were your instructions clear? Was the model too difficult? Despite students displaying engagement throughout the lesson, now left to their own devices you seem to have reached an impasse.

This narrative may sound familiar to many educators but one solution to mitigate is found in the process of developing metacognition. But what is metacognition and why is it the current hot topic in education?

What is metacognition?

Metacognition is not new to education and has long been considered a low-cost, high-impact strategy and following the Covid -19 pandemic, the Department for Education (DfE) and the Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) have been further highlighting the need to teach metacognitive strategies.

Simply put, metacognition is thinking about thinking; it actively engages you in considering your thinking processes. This concept not only involves thinking about one’s thinking but having the knowledge and control to understand your thinking and learning processes.

Teaching metacognition allows students to develop the tools required to retrieve and deploy strategies that they have been taught (Flavell, 1979). By equipping students with the tools that allow them to be in control of their learning, you demonstrate to learners that learning is an active process that they can achieve (Cubukcu, 2009). It is important to remember that all students are metacognitive learners, but these skills need to be explicitly taught to enhance their metacognitive capabilities.

Researchers have identified two components of metacognition: metacognitive knowledge and self-regulation (Brown, 1987). Metacognitive knowledge involves the information we hold about our own learning, such as our learning strengths and weaknesses or knowing what strategies are available to us.

On the other hand, self-regulation involves a set of activities that support learners in controlling their learning and, at the centre of self-regulation, are three fundamental skills:

- Planning – Understanding how to approach a task before you complete it

- Monitoring – Monitoring your progress and understanding of the task

- Evaluation – Reviewing your learning experience and the outcome

But what does this look like?

A key aspect of metacognition is processes. Ensuring that learners are aware of the processes required to successfully complete a task is critical to their learning. Therefore, it is important to ensure that processes are being explicitly taught and narrated.

Planning

At this stage, support students with understanding what they are being asked to do; what will support them in achieving this; and how they can draw upon previous learning. Model how they would think about this stage of the task, not just what they should do.

Monitoring

At this stage, support learners with reflecting on their progress as they work their way through the task, especially when they become stuck or answer incorrectly. Pause the task and prompt questions about their current thinking processes; question if there are different ways to complete the task; or what they think they could do if they are stuck.

Evaluating

At this stage, support learners with understanding their response and making links back to the task. This stage is critical in developing their reflective practice but also supports developing resilience. If they have not achieved the expected outcome, use prompt questions to explore their understanding of the process they used and what they could do differently.

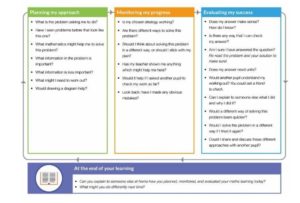

The EEF’s Think Aloud Planning Tool (EEF, 2022) provides a clear framework with questions for students to consider at each stage.

If you would like to know more about metacognition, BDSIP’s Professional Learning Community for SEND will be exploring the concept in more depth in the spring term.

Hannah Hamid

Senior Inclusion Adviser

References

- Brown, A. L. (1987). Metacognition, executive control, self-regulation, and other more mysterious mechanisms. In F. Weinert & R. Kluwe (eds.) Metacognition, motivation, and understanding. Hillsdale: Erlbaum, pp. 65–116.

- Cubukcu, F. (2009). Metacognition in the classroom. Procedia –Social and Behavioural Sciences, 1(1), pp.559-563.

- Education Endowment Foundation (2022). Moving forwards and mobilising metacognition. [online] EEF. Available at: https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/news/eef-blog-moving-forwards-and-mobilising-metacognition [Accessed 6 Oct. 2022].

- Flavell, J. H. (1979). Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive developmental inquiry. American Psychologist, 34(10), pp.906-911.