The focus on diversity in the science curriculum is nothing new. Indeed, prior to the current discussion around race and social justice, teachers of STEM subjects were grappling with the gender gap and in response to this, Teach First launched their STEMinisim campaign in February 2020 with Missing Elements: Why ‘steminism’ matters in the classroom which highlights the following stark statistics:

- When looking specifically at STEM-based careers, only 22% of roles are occupied by women. At management level this drops to just 13%.

- 49% of British adults were unable to name a female scientist that was dead or alive.

- In a sample of Double Science GCSE specifications from the biggest three exam boards, there were forty mentions of male scientists – or concepts and materials named after them – while there were only two mentions of women.

The lack of female models in science will have a likely influence on whether female students see a place for themselves or whether they look to scientific careers at all. Indeed, to quote Toni Schmader, who studies stereotypes and social identity at the University of British Columbia, “Stereotypes reflect what people see in everyday life and can play an important role in constraining children’s beliefs of what they can/cannot do’ (Yong, 2018). Miller’s 2018 meta-analysis of five decades of Draw-A-Scientist studies found that ‘children’s depictions of scientists … have become more gender diverse over time, but children still associate science with men as they grow older’. This goes some way to illustrating the fact that if our curriculum, and society at large, places an emphasis on representing diversity, there will be an impact.

Representation within science is important. I will never forget a conversation with a young science teacher in a school I was supporting where she asked if I had taught science in the school she had attended. Asides from making me feel simultaneously old and surprised at being remembered by someone I hadn’t actually taught, I was taken aback by her recollections of seeing someone who looked like her, and left wondering whether that had influenced her to later follow the same path.

As we now explore wider issues around diversity in the curriculum, there is a need to ensure that this is done in a coherent and meaningful way, which may feel like a daunting task. So let’s reframe it: How can we make the curriculum more relevant for our students through careful consideration of the examples and role models that we use?

Celebrating Diversity

Our first consideration is what we mean by the term ‘diversity’. Merriem-Webster defines it as ‘the inclusion of people of races, cultures. etc. in an organisation or group’. However, when we consider the nine characteristics of the Equality Act (2010) , this definition could be seen as too narrow. Consequently, we would suggest the more comprehensive definition offered by Deer (2020) in ‘Promoting equality and diversity in the classroom‘:

Equality and diversity, sometimes called multiculturalism, is the concept of accepting and promoting people’s differences. The fundamental goal when promoting equality is to raise awareness and make sure that all individuals are treated equally and fairly. This is regardless of their age, gender, religion, disability, sexual orientation, or race.

So in what ways could we diversify the science curriculum to ensure that we promote representation? Immediate thoughts could link to the inclusion of:

- diverse representation within texts, videos or website links being shared

- diverse role models as part of your setting’s STEM initiatives

- scientific contributions of under-represented groups being highlighted throughout the year (as opposed to a focus during Black History Month).

The danger is that these practices can link to a ‘tick box’ implementation rather than a holistically, integrated curriculum implemented year on year. Sophie Thompson captures the spirit of this well in her article for The Headteacher, when she says, ‘The goal … is to build a curriculum that embraces, celebrates, highlights and foregrounds diversity.’

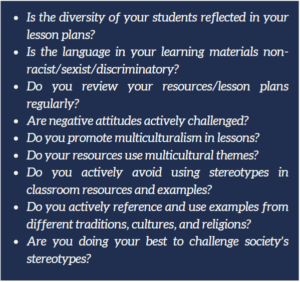

Deer (2020) proposes a series of questions that can help to review the diversity reflected within your curriculum. These include:

The benefits of increased diversity and representation within the curriculum include:

- Greater understanding of and between different cultures

- Enrichment of the school community by sharing experiences of different people.

- Greater engagement with the curriculum.

All that said, we need to bear in mind the advice of Mark Hughes in Embedding Equality and Diversity in the Curriculum: a physical scientist’s practitioner’s guide. Hughes warns us to avoid the assumption that ‘all students from a particular group will either act in the same way or have the same needs and aspirations’. He suggests we should establish pupil voice as part of the development process, since students ‘can also be a great source of ideas for changes you may wish to make to your curriculum. They may have experience of what has or has not worked.’

Staff Training

Staff training is necessary to ensure that meaningful curriculum changes occur to reflect diversity and representation. The Science Museum Group provide support and training for teachers through the ‘collaboration between schools, young people, their families, museums and science centres’. Their aim is to ‘find ways to connect school science with students’ diverse identities and lives.’

The Association of Science Education series of Best Practice Guidance Documents provides important advice on key aspects of the teaching and learning of science. They are short, easily accessible guides that contain links to further support. They include advice on many aspects including best practice guidance on diversity and equality within science.

The Barking and Dagenham Race and Social Justice Programme has a curriculum workstream. Using audits, school facilitators have identified emerging best practice that can be shared across settings and areas where further training would be beneficial to support the development of our local strategy. Further information about the offer will be made available to schools in due course.

In summary, diversity fosters innovation and science needs creative innovators. It is therefore imperative to create a climate in which our differences are valued, reflecting the strength diversity brings to our curriculum.

If you would like to explore further support in relation to this issues raised in this article, please contact Paul Hammond, Senior School Improvement Adviser (Secondary).